Estimated reading time: 6 minutes

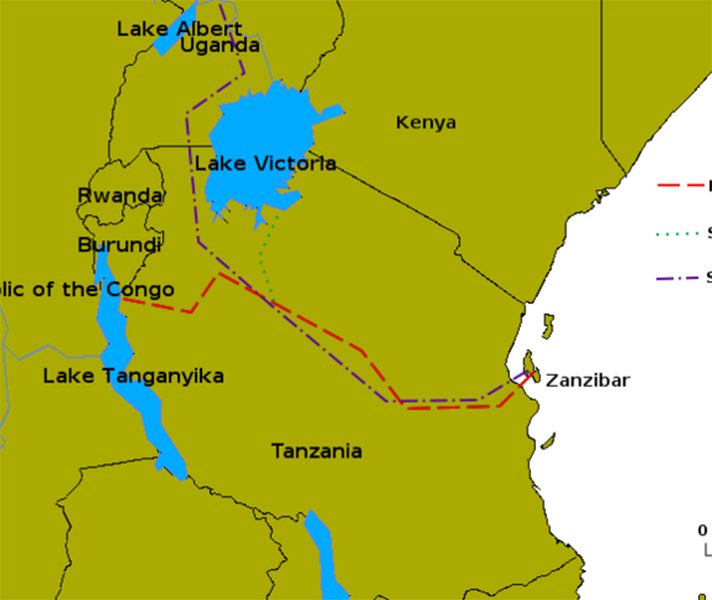

Driven by the expansionist turbines of Queen Victoria’s British Empire, the 19th century saw more progress in mapping and surveying Africa’s mysterious interior than the previous three centuries combined. The interior was extremely dangerous for Europeans, who succumbed to malaria, dysentery and sleeping sickness, or died violently at the hands of indigenous people.

Those explorers who made it back to their native soil became mythic heroes. In truth, most of these men faced harsh challenges early in life, which shaped them into tenacious, stubborn individuals with a finely-tuned knack for survival. The empire’s pathfinders honoured their queen wherever they found iconic landmarks, and her name still graces the world’s largest waterfall, Victoria Falls, and the largest tropical lake, Lake Victoria. Who were these intrepid, resilient men behind the legends that sprang up around them?

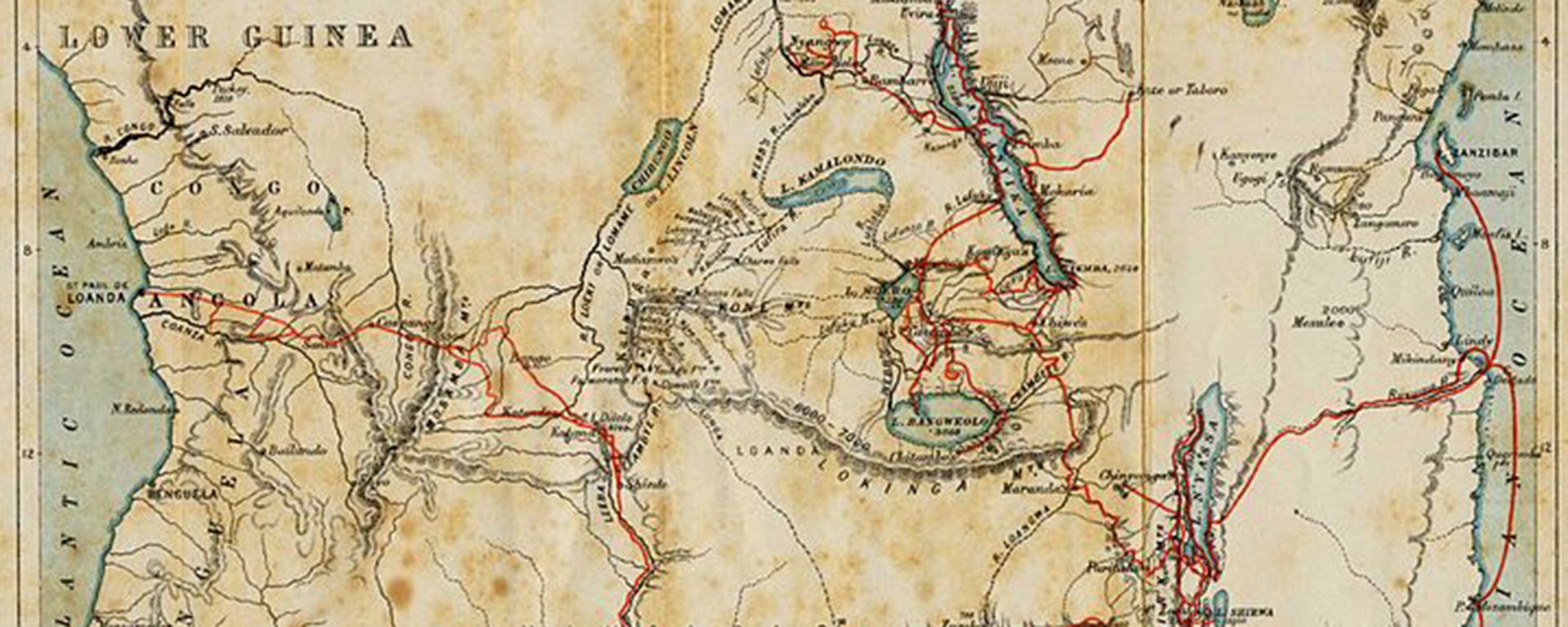

David Livingstone (19 March 1813 – 1 May 1873)

Dr David Livingstone is perhaps the best-known of the Victorian explorers. Missionary martyr, working-class hero, scientist and passionate anti-slavery crusader, his empathy for the suffering of others was inspired by his own experience of poverty. He laboured through 12-hour shifts in a cotton mill from the age of 10 to 26, eventually saving enough to study medicine in London, where he joined the London Missionary Society. Livingstone’s missionary work had one aim: to destroy the slave trade by opening legitimate trade routes and converting indigenous people to Christianity. His motto ‘Christianity, Commerce and Civilization’ is inscribed on his statue at Victoria Falls, which he described as “so lovely [it] must have been gazed upon by angels in their flight.”

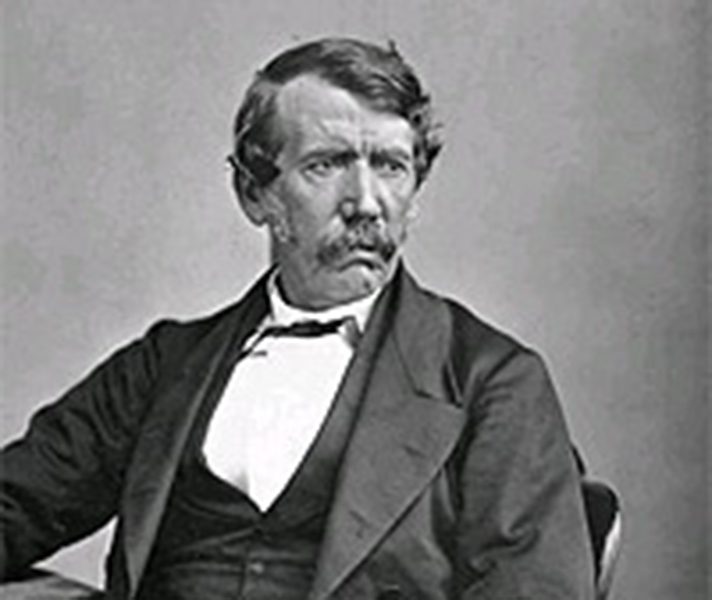

In addition to putting Victoria Falls on the map, Livingstone found Lake Malawi, surveyed Lake Tanganyika, charted the course of the Zambezi and was the first European to cross the sub-continent. Unlike most of his contemporaries, Livingstone’s respect for indigenous people earned him the hospitality and assistance of many chiefs. Although he is called ‘Africa’s greatest missionary’, he only officially converted one African: Chief Sechele of the Kwena, a powerful Sotho-Tswana clan in southern Africa. Livingstone taught the chief to read; Sechele translated the Bible into his native tongue and did more to promulgate Christianity in southern Africa than any European missionary could have done.

At the height of his influence, Livingstone led the Zambezi Expedition to open up the river for commerce. But the Zambezi River cannot be navigated past the Cahora Bassa rapids and the expedition was considered a disaster. It cost Livingstone his reputation and his beloved wife, Mary, who succumbed to malaria while visiting him. On his final expedition, Livingstone lost contact with the outside world for six years, and the New York Herald sent Henry Morton Stanley to find him. When they met, Stanley uttered the famous greeting, “Dr Livingstone, I presume?”. Livingstone was weak from repeated fevers and dependent on the hospitality of Arab slavers but refused to leave Africa.

He died in a Zambian village in 1873. His devoted servants, Chuma and Suza, buried his heart under a mvula tree and then carried his body over an epic 1600km (1 000 miles) to the coast. His remains were interred at Westminster Abbey in London, and reports of Chuma and Siza’s devotion alongside the publication of his last journal restored Livingstone’s reputation. In 2002, he was named one of the Hundred Greatest Britons in a national vote.

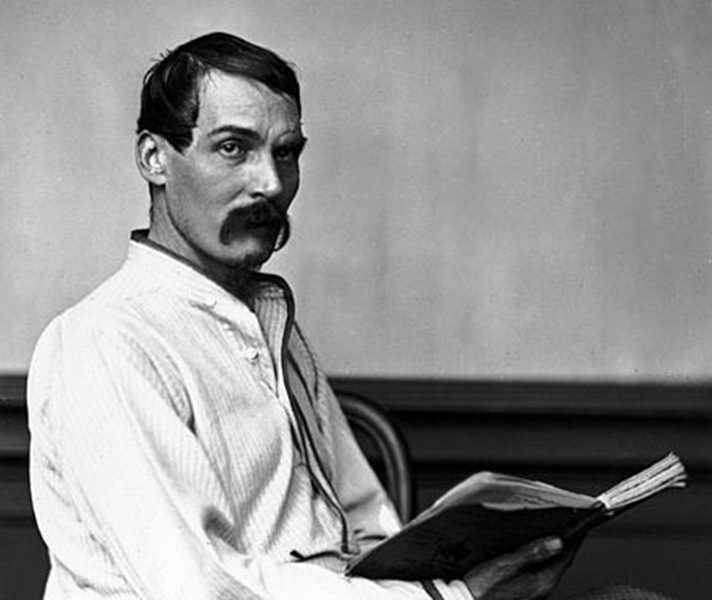

Richard Francis Burton (19 March 1821 – 20 October 1890)

Captain Sir Richard Francis Burton was easily the most controversial Victorian explorer. He was admired as a soldier, cartographer and exceptional linguist but took great delight in antagonizing anyone in authority over him, publishing translations of erotic Oriental literature that scandalised the public and, as a skilled fencer, challenging to a duel any man who criticised him.

In 1854, he led an expedition to explore the Somali region. His party included John Hanning Speke, who would later accompany Burton on his most famous journey to the Great Lakes in Central Africa. Over 200 Somali warriors attacked the party before it even set off. Speke was captured and severely wounded before escaping. Burton was impaled with a spear, the point entering one cheek and exiting the other, leaving scars that are clearly noticeable on his portraits and photographs.

Two years later, Burton set off to find the ‘inland sea’ he’d heard described by Arab slavers. Speke accompanied him and, again, their expedition seemed ill-fated – porters stole supplies and deserted in droves, equipment was lost and damaged, and both Burton and Speke suffered a barrage of tropical illnesses. Burton was unable to walk for part of the journey and Speke was temporarily blind when they eventually reached Lake Tanganyika in 1858. Without their surveying equipment, there was little they could do but Speke recovered his sight and went on to locate Lake Victoria while Burton remained in camp, too ill to travel. The men returned to Britain separately and began the most famous feud of the era. Speke reached London first and presented his findings to the Royal Geographical Society, claiming that Lake Victoria was the source of the Nile. Burton was enraged to find Speke being lauded for such a find and his own role in the expedition largely negated.

Burton’s detailed notes on geography, languages and customs became an invaluable resource for later explorers, like David Livingstone and Henry Morton Stanley. After a colourful diplomatic career beset by intrigue and controversy and publishing both the Kama Sutra and Arabian Nights, Burton was buried beside his wife, Isabel, in a tomb shaped like a Bedouin tent in the cemetery of St Mary Magdalen, London.

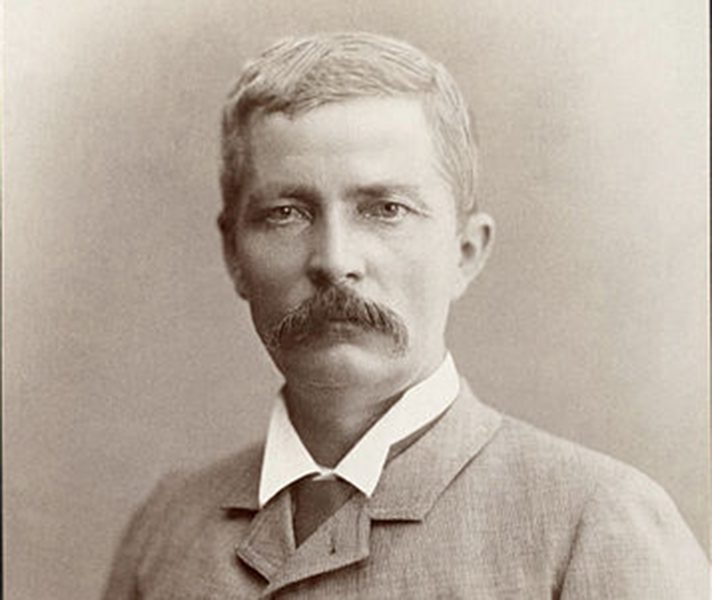

Sir Henry Morton Stanley (28 January 1841 – 10 May 1904)

Sir Henry Morton Stanley was born John Rowlands, the illegitimate son of a teenage servant girl. When he was six, Stanley became an abused inmate of St Asaph Union Workhouse. At 18, armed with a basic education, he worked his way to the United States where he met his benefactor, Henry Hope Stanley, who changed his name and his fortune. After a short stint as a soldier, Stanley became a journalist. His forthright style earned him an exclusive retainer with the New York Herald.

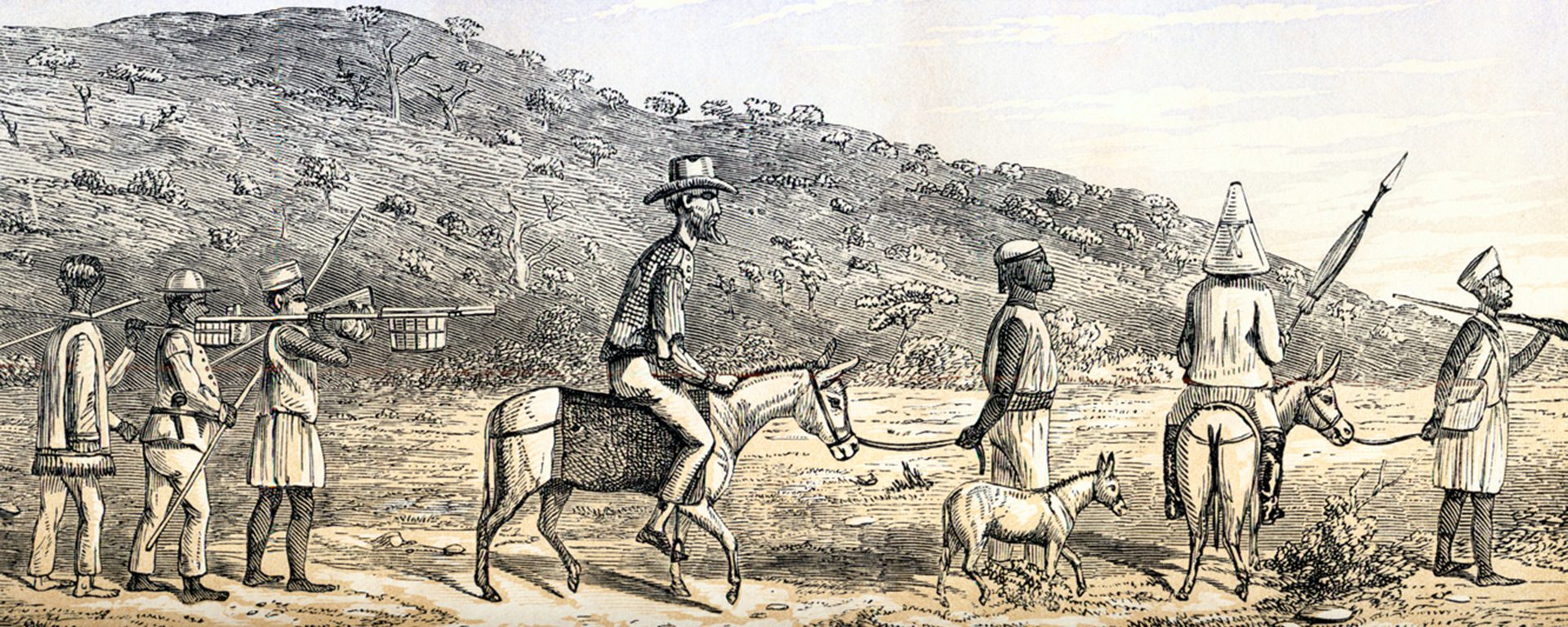

In 1869, the Herald sent Stanley to find David Livingstone. Outfitted with the best money could buy, Stanley set off on the 1 100km (700 mile) journey with 200 porters and a thoroughbred stallion that died within days. Stanley was notoriously brutal towards indigenous people and porters deserted him, carrying away supplies in the night. He survived the nightmarish journey and secured a place in history when he found Livingstone in 1871. In 1874, the New York Herald and Britain’s Daily Telegraph backed Stanley in another adventure: to chart the course of the Congo. This was an exceptionally challenging expedition, even by Victorian standards. After 999 days, the party reached the mouth of the Congo River. Of the 356 people who began the journey, only 114 survived; Stanley was the only European.

In 1866, funded by Belgian King Leopold II, Stanley set out to rescue Emin Pasha, the governor of Equatoria in southern Sudan. After two trying years, the party reached Emin. On the return journey, they charted the Ruwenzori Range and Lake Edward, eventually delivering Emin to safety in 1890. Stanley’s disinterest in the welfare of indigenous people allowed the Europeans in his party to behave with unspeakable cruelty. Tales of their misconduct revolted Victorian society, most notoriously the purchase of an 11-year-old girl so that one British gentleman could document how cannibals cooked and ate her. This tainted legacy haunted Stanley to his death in London in 1904 and provided the inspiration for Joseph Conrad’s novel Heart of Darkness, itself the inspiration for Apocalypse Now.

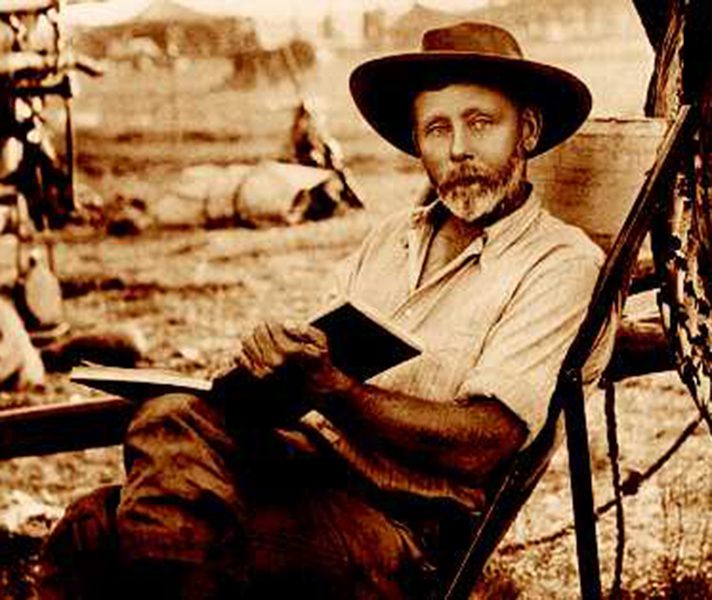

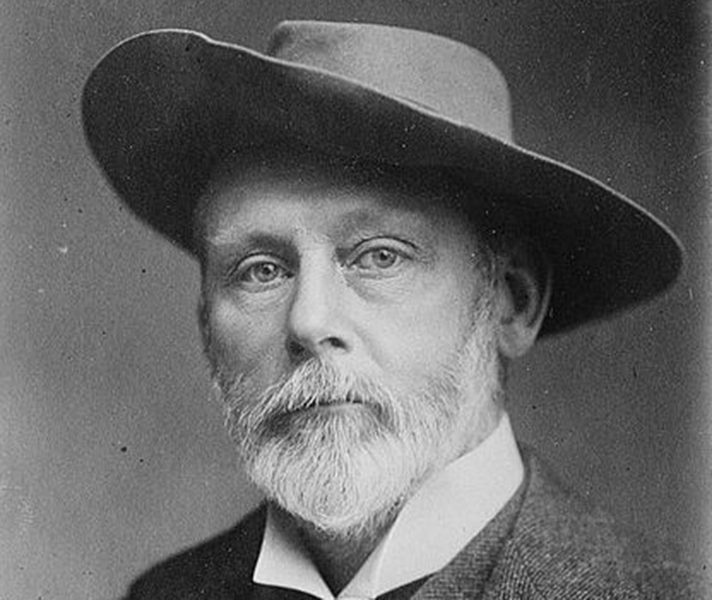

Frederick Courteney Selous (31 December 1851 – 4 January 1917)

Frederick Courteney Selous was born in London to an aristocratic family descended from French Huguenots. His childhood passion for natural history focused his attention on Africa and the expeditions of his hero, Dr David Livingstone.

In 1872, aged 19, Selous travelled from the Cape of Good Hope (now the Western Cape in South Africa) to Matabeleland (now Zimbabwe), where the king of the Ndebele gave him permission to hunt on tribal land. For the next two decades, Selous made his living hunting ivory, exploring a vast area stretching from modern-day Namibia and South Africa to southern Sudan. He donated what became known as the Selous Collection of 524 mammals to the Natural History Museum in London and almost single-handedly charted the area that became modern Zimbabwe. In 1890, Cecil John Rhodes recruited Selous to lead a road-building expedition over 640km (400 miles) of mountains, swamps and forests to Mashonaland (northern Zimbabwe). Selous famously delivered the whole party intact and in good health.

From the First Matabele War in 1893 to the East Africa battlefields of World War I, Selous served the British army in Africa. He was a modest man who drank tea, had the tracking skills of a born African, and was a legendary big game hunter in an era before telescopic sites and high-powered rifles. Selous was ironically also one of the first conservationists, recognising and publicising the decline in southern Africa’s wildlife due to unregulated hunting.

At 42, Selous married 20-year-old Marie Maddy in England, who bore him three sons. He already had three children with African wives and, in 1896, moved his English family to Matabeleland. When he was 64 years old, World War I erupted, the conflict spilling into East Africa. Selous died in action on the banks of the Rufiji River, struck in the head by a German sniper’s bullet on 4 January 1917. US President Theodore Roosevelt wrote of his death: ‘He led a singularly adventurous and fascinating life… [and] closed his life exactly as such a life ought to be closed, by dying in battle for his country while rendering her valiant and effective service.’

Today, you will find a simple bronze plaque marking his burial place in Nyerere National Park (previously Selous Game Reserve). The reserve is a fascinating and complex wilderness, still untamed today and rewarding the travellers who dare to explore it.